Sir John Vickers, the architect of the Government’s post-financial crisis banking reforms, has dramatically escalated his battle with the Bank of England over the future safety of the UK’s big banks.

Sir John said this was “ironic” given the Chancellor, George Osborne, has often spoken of safe domestic banking as a way to address the “British dilemma” of how to protect the taxpayer while keeping the UK a competitive base for global banking.

Sir John also leaves the Bank of England’s top officials in no doubt that their capital proposals fall well short of what the Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) – whose conclusionswere accepted by the Chancellor – wanted.

Sir John has previously warned that the Bank of England was in danger of under-cooking its capital requirements, but this latest intervention expands considerably on his original objections and will ratchet up the pressure on the Bank to think again.

Sir John was the chair of the ICB, established by Mr Osborne in 2010, which recommended that banks should be forced to “ring-fence” their retail banking arms and also to have significantly larger capital buffers on their balance sheets than they did going into the global financial crisis.

“We in the ICB wanted to go above the global standard” he said. “With the City of London [being] a major financial centre you want to protect the British taxpayer”.

“Lloyds apart, there seems to be very little extra capital required by the Bank’s proposals compared with what’s globally required, whereas we were trying to go well above and beyond the global”.

Sir John added: “The Bank of England has pitched these size thresholds [for the applicability of its new capital buffer] so high that for some banks the global buffers outdo the domestic buffer which is a bit ironic”.

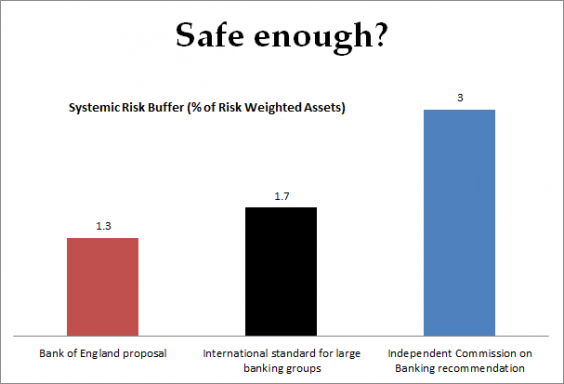

The specific focus for Sir John’s concern relates to the Bank’s proposals for how big the size of a new “Systemic Risk Buffer” (SRB) of capital for ring-fenced banks and large building societies.

Sir John says the ICB wanted this to be equivalent to 3 per centof ring-fenced banks’ so-called “Risk Weighted Assets” (RWAs). But according to a letter written by Mr Carney to the TSC on 5 April the Bank of England is proposing to require the SRB to be only 1.3 per cent of RWAs on average. Sir John said the difference was “very significant” and also noted that the global buffer would average 1.7 per cent for UK banks.

Sir John is calling for the Bank to change its mind and impose the 3 per cent SRB originally demanded by the ICB. This would require banks to raise more capital, either by asking their shareholders for more cash or, more likely, by retaining profits and paying smaller dividends. Such a requirement would be fiercely resisted by banks.

Sir John also criticises assumptions in the economic modelling which the Bank of England used to justify not setting the SRB higher, saying that the policy was based on estimating costs and benefits of higher capital in “normal” risk conditions. “One would not base flood defence policy on cost-benefit analysis of improving flood defences in average weather conditions” he said.

In January the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee published a consultation paper on the framework for the SRB. The deadline for responses was last Friday. The Bank has said it will make its final decision by the end of May.

In his June 2015 Mansion House speech George Osborne said that the “British dilemma” was “being host for global finance without exposing our taxpayers again to the calamitous cost of financial firms failing”.

The Chancellor said that “restoring the Bank of England’s role in the heart of supervision, in ring-fencing retail banking and insisting on much better capitalised firms, we have made enormous progress in solving that dilemma”.

When banks get into trouble they need a decent-sized slice of capital on their balance sheets in order to absorb their losses. If the capital slice is too small the bank risks going bust and governments can be forced to prop up the banks with taxpayers’ money.

The previous Labour government was forced to inject £17bn into Lloyds and £40bn into RBS in the 2008-09 financial crisis to prevent them going bust and wreaking catastrophic damage on the wider economy. And the total amount of state support in the form of cheap Bank of England loans and government guarantees extended to the UK financial sector was more than £1trillion.

A spokesperson for the Bank said they had nothing to add to the consultation document they originally published in January and to the evidence given by Mr Carney to the TSC earlier this month.

Source: The Independent

Leave a Reply